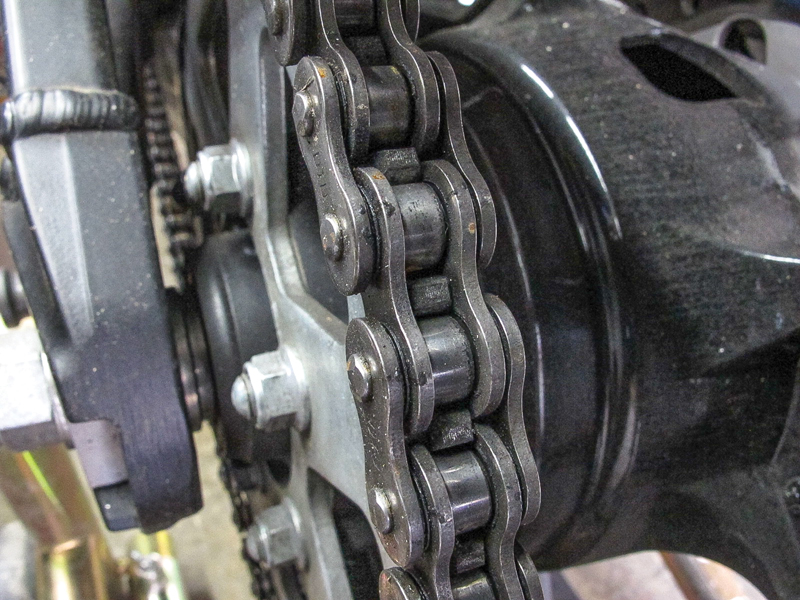

Take a look around most dealership floors, bike night parking lots or a race paddock, and the vast majority of motorcycles will be wearing a chain and sprockets for their final drive. Belts and driveshafts have their perks, but chains are the dominant drivetrain thanks to their low production cost, efficient power transmission and easy gearing changes and component replacement.

Chains basically come in two categories: unsealed or standard roller chain, and sealed or O-ring chain. Unsealed chains are commonly found on vintage bikes, small-displacement economy rides and off-road motorcycles. They’re what you see on bicycles and conveyor belts, and even the treads on a bulldozer are a type of unsealed chain. Standard chain is just a series of plain bearings made of metal links and nothing else. That means it’s up to you to apply lubricant to keep the parts from grinding themselves into dust, and you have to do it every few hundred miles. Even then, reducing friction between high-wear components like the link pins and bushings is difficult, and as a result unsealed chains wear quickly, necessitating frequent slack adjustments and replacement.

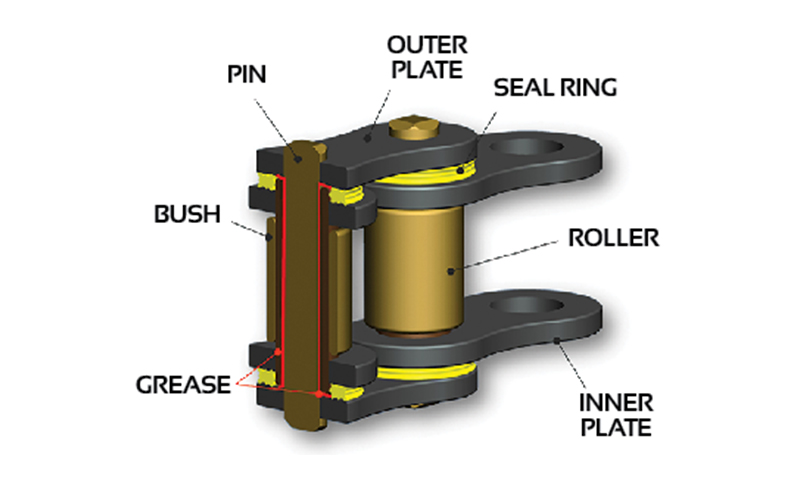

Sealed chains, as the name suggests, have rubber seals sandwiched between the side plates and inner links, sealing in grease that’s sucked in around the pins via vacuum when the chain is manufactured. The O-rings seal the grease in and keep dirt and water out, ensuring the pins and bushings are bathed in lube, which greatly reduces wear and extends the life of the chain. This arrangement also means less frequent and lighter applications of chain lube, since all you’re doing with that can of aerosol is keeping the O-rings moist and pliable and preventing the metal links from corroding.

Sealed chains were introduced in the late 1970s and revolutionized chain maintenance by greatly reducing the need for lubrication while simultaneously increasing the life of the chain by up to tens of thousands of miles. More recently, other seal styles have been developed, most notably the X-ring. Here’s the idea: When that chubby little O-ring gets squeezed between the plates, it creates a fair amount of surface area that results in a small amount of drag every time the chain link pivots. That drag saps power getting to the rear wheel. With an X-ring chain, the sealing ring’s profile resembles an “X.” The X-ring is more readily compressed between the plates, and its shape provides four sealing surfaces around each link pin (instead of two), but with less total surface area, resulting in less drag.

If evaluating the drag on your chain seems like the kind of obsessive minutia only a racer would think about, you’re right. X-ring technology was developed for the track and adapted for the street, where the better sealing of the X-ring helped increase chain life even more. As a track-bred product, X-ring chains are typically made from harder, stronger metals and may have weight-reducing features like hollow link pins and thinner side plates. With all those virtues, however, comes a higher price.

Generally speaking, the better sealing (and thus service life) a chain offers, the more expensive it’s going to be. That being said you may be tempted to slap a standard unsealed chain on your bike because it’s cheap, but the upfront savings simply isn’t worth the cost of increased maintenance and more frequent replacement. Unsealed chains still make sense on smaller, less powerful machines that will log fewer miles, but for regular road use a sealed chain–whether it’s an O-ring type or some other variety–is definitely the way to go.