“There is no perfectly shaped part of the motorcycle and never will be, but when you come as close as these instruments take you, remarkable things happen, and you go flying across the countryside under a power that would be called magic if it were not so completely rational in every way.” – Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Motorcycle mechanics. An unquestionably intimidating subject. As a 21-year-old college student, I never fathomed I’d become completely fascinated by the sensation of turning a wrench. I didn’t think I was “mechanically minded.” Whenever issues arose with the old vehicles I drove, my first instinct was to call my dad, see if he could guess how bad the issue really was, and help me figure out if I could keep driving on borrowed time, or if a trip to the hole-in-the-wall mechanic shop was necessary.

That was the case until I was forced into the realm of wrenching on my own machines during the early days of the pandemic. I had purchased a 1986 Kawasaki 600 Eliminator for $850. It was the first streetbike I’d ever owned, and certainly the most raw power I’d ever experienced. I loved that bike. It was shiny, loud, and fast enough to rip on I-80 through the Bay Area.

So, what was the cause of the Eliminator’s sad demise? A boy’s advice, of course. This friend of mine was under the impression that Sea Foam motor treatment could not be overdone. That’s how a full quart of it ended up in my half-full 3-gallon tank. I knew nothing of the impending consequences.

Pretty soon, coolant started leaking out of the water-pump drain, white smoke was blowing from the tailpipe, and eventually, the bike quit altogether. I felt backed into a corner. I had no idea where to begin, and I was afraid of making the problem worse. After two weeks of countless phone calls to friends, seeking help on social media, reading Xeroxed manuals, and digging through forums, I concluded that I could not fix the problem myself. In the interim, I changed the plugs, tried to clean the carbs, and drained and cleaned the fuel tank. But the blown head gasket was way beyond my skill set. At the time.

During those heart-breaking struggles, I came to realize three important things about wrenching on older bikes: 1) Everything you need to know about how to fix, replace, or tune up just about anything is available to you online. 2) The few tools you need to get started are cheap and easy to acquire. 3) You don’t need a background in wrenching to become proficient at it. Your family didn’t have to raise you doing this activity every Sunday afternoon. Anyone can fix up an old bike as long as you’re willing to face – head on – the mental challenges that come with it.

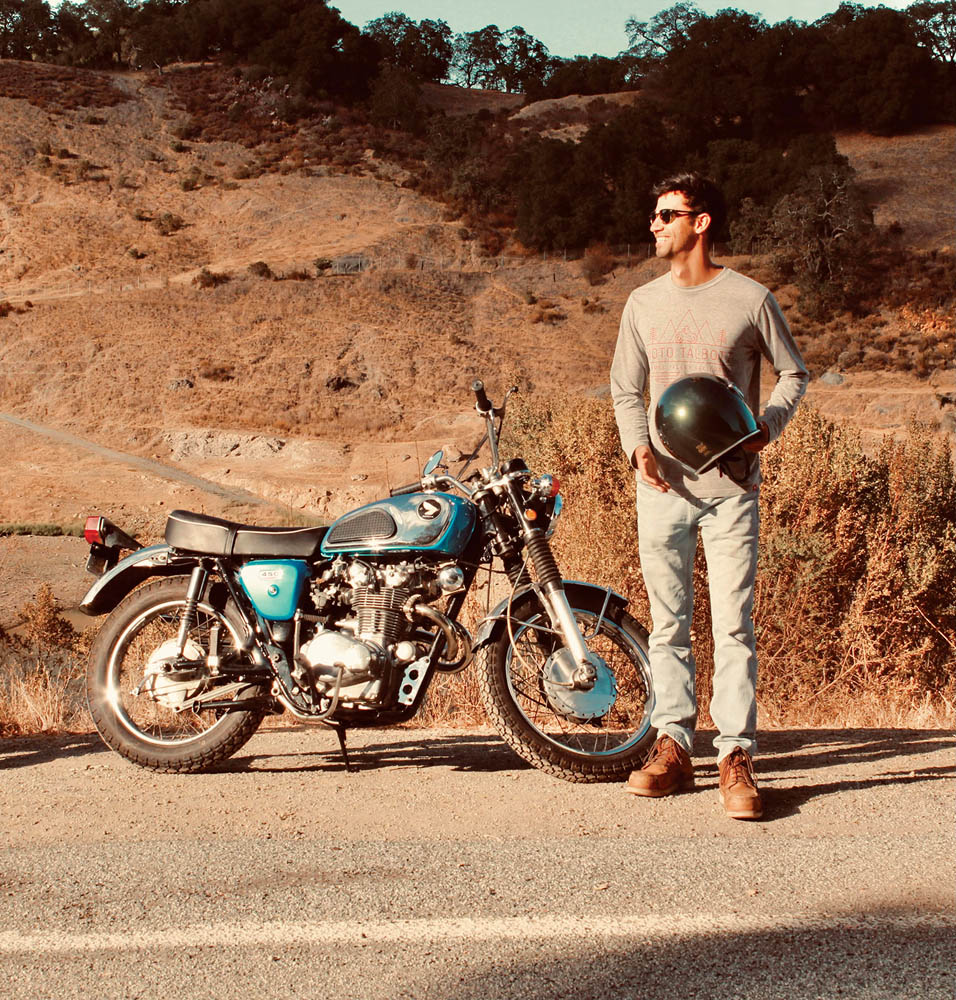

Why had no one told me this before? Why was I always so intimidated by the notion of mechanics? Why is there such an intense gatekeeping attitude surrounding these skills? Well, if a broke college student like me can take a basket-case 1971 Honda CL350 from completely disassembled to a running head-turner in just eight months, then anyone can. If wrenching has always been something you’ve shied away from for fear that you’re not competent enough, or you might do more harm than good, then take heart.

What does it take to begin the journey of wrenching on an old bike? Start with a set of basic mechanic’s tools and a clean work area. Hopefully your bike has a centerstand, and if not, you can buy an inexpensive jack or lift from Harbor Freight. Have plenty of WD-40, Windex, grease, and clean rags at the ready. Invest in the factory service manual for your bike, as well as a Clymer or Haynes manual. (There is a tangible quality difference between older Clymer manuals and freshly written ones. The closer the publication date gets to the birth year of the motorcycle, the better.) Accept the fact that you’ll make mistakes and bust a few knuckles. The learning process is rarely linear.

The most burning question I had when I started my journey was, “How difficult is this really going to be?” The honest truth, which few people are willing to share, is that it’s not difficult. Not really. Most of it comes down to lefty loosey, righty tighty. Even the more complicated stuff, such as rewiring your bike, comes down to following a diagram that’s no more complicated than the instructions to put together an Ikea bookcase.

Motorcycles, especially old ones, are put together in a way that is meant to make sense. The physical aspect of motorcycle mechanics is not difficult to grasp. The difficult part is confronting your own mindset and staying calm when the machine makes you feel like the world is against you. You need to have enough commitment to yourself and your learning journey to finish what you started.

Like many before me, Robert M. Pirsig’s masterpiece Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance has had a direct and lasting impact on the way I approach wrenching. As he wrote, “It’s so hard when contemplated in advance, and so easy when you do it.” Keep that in mind. Simply trying is the most powerful move you can make.

Get started on your mechanical journey with simple, hard-to-mess-up routine maintenance tasks, such as an oil change and changing the spark plugs. They’re cheap, and both can be done in about an hour or two by someone who’s never held a wrench before. They’ll require you to do a little research and make at least one trip to the parts store. Get comfortable speaking with the humans working behind the counter and asking for what you need. Get into the groove of following instructions, whether that’s from a shop manual, a YouTube video, or a friend. Savor the satisfaction of knowing you’re making an effort to take care of the machine that takes care of you.

When I asked Armon Ebrahimian, the founder of Save Classic Cars (saveclassiccars.net), a website “dedicated to keeping classics alive” that also lists vintage cars and motorcycles for sale, what advice he would give an aspiring backyard mechanic, he said: “One project at a time. It’s tempting to blow apart an entire bike or car, but this is how people get in over their heads. Start small. Take something small apart and put it back together. Don’t take something else apart until you’ve successfully put that first project back together.”

What happens when your bike breaks down? Pause. Breathe. Think about what you know and what you don’t know. Then get curious about what you don’t know. Use the tools of observation you learned in middle school: Take note of what you see, hear, smell, and feel. (Please don’t taste any part of your motorcycle.) Use those observations to make a hypothesis, and then search for answers in your manuals, in online forums, and on YouTube. Whatever issue you’re having, it has already been diagnosed, fixed, and written or talked about by someone somewhere, so keep digging. Go through this process even if you end up deciding to take your bike to a mechanic’s shop. At least you’ll know more about what went wrong and why, and you’ll be better prepared the next time a similar issue occurs.

It’s helpful to eliminate time limits. If your motorcycle is your primary means of transportation, then a timely fix is important. But if not, removing the pressure of time reduces stress, which frees up mental bandwidth and helps keep things moving forward. Then an extra trip to the parts store becomes just another step in the process rather than a frustration. Just don’t confuse a lack of time pressure with procrastination.

Once, a sharp part of the frame on my 1998 Honda Shadow ACE 1100 wore through the insulation of one of the battery cables, which grounded out and caught fire. My bike sat for two weeks before I mustered the courage to deal with it. When I finally took the seat off, it took about five minutes for me to diagnose the problem and another five for me to solve it. I could have been riding that whole time, but instead I wallowed in my anxiety about the issue.

This experience taught me two things. One, effort is essential, and any amount of it will be fruitful in some way. Two, effort becomes knowledge. Every time I pick up a wrench, I learn something new, and the process becomes more familiar and less daunting.

Pirsig nailed it: “I’ve heard it said that the only real learning results from hang-ups, where instead of expanding branches of what you already know, you have to stop and drift laterally for a while until you come across something that allows you to expand the roots of what you always know.”

When gathering clues and deducing what the issue may be with your motorcycle, sometimes the answer won’t come easily. These things can be very stubborn. You just have to be a little more stubborn. Relating a story by Pirsig, Matthew B. Crawford writes in his book, Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry Into the Value of Work, “This is the Truth, and it is the same for everyone. But finding this truth requires a certain disposition in the individual: attentiveness, enlivened by a sense of responsibility to the motorcycle. He [She] has to internalize the well working of the motorcycle as an object of passionate concern. The truth does not reveal itself to idle spectators.”

When I asked Mike Dubnicki, co-founder of Mazi Moto (mazimoto.com), a restoration shop in San Francisco, what advice he would give an aspiring backyard mechanic, his response was similar to Armon’s: Start small and keep it simple. He also said, “have fun and be safe.” Take that to heart. We’re here – in the garage or on the sidewalk, with tools out and fingers greasy – because it challenges us. Because it fills us with a certain wholeness that’s all too rare in today’s world.

So, go ahead. Pick up a wrench, dive in, and enjoy getting a little dirt under your fingernails.

Hannah Hill is a student at California State University Maritime Academy in Vallejo. She aims to create a community space someday where riders of all types have a place to wrench and connect with other like-minded humans. You can find her on Instagram: @rollinghillmotos.

The amount of confidence that fixing things can give you is priceless. Start small, make mistakes, learn and tackle something bigger.